Overview of Fundation Models

With the development of the times, the application of foundation models in various fields is expanding. This article tries its best to sort out various materials and will give a brief overview of foundation models from the aspects of concept definition, type classification, training and application.

If you want to understand foundation models but lack basic knowledge or feel that you have no idea where to start, then reading this article may help you.

Concept Definition

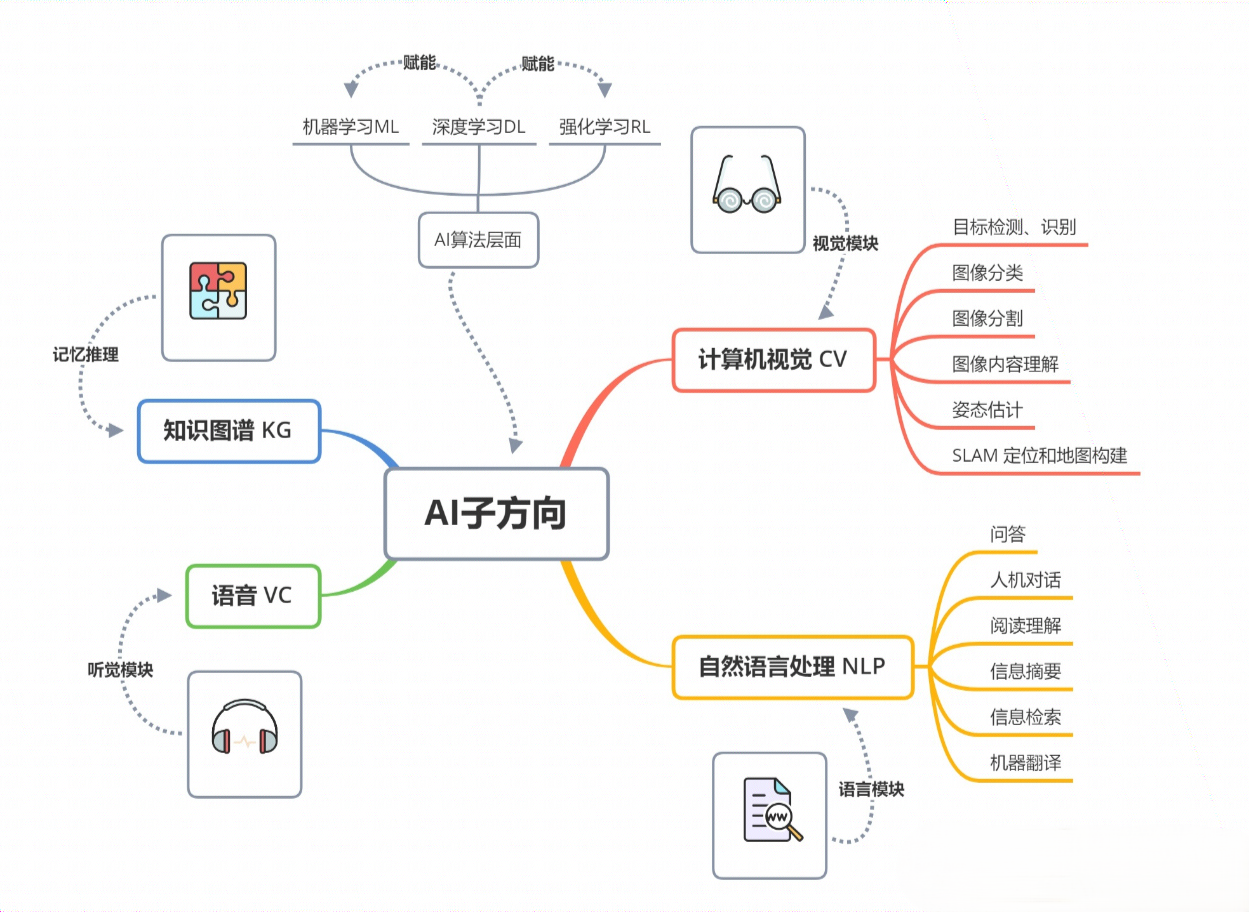

Main Concepts of Artificial Intelligence

Application Field

Algorithm

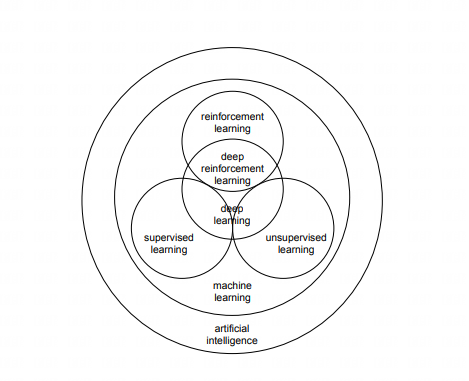

Machine Learning ( ML ) : Machine learning is a core subfield of AI that allows machines to learn and predict from data.

Supervised learning: Learning labeled data and predicting labels for unseen data.

Linear Regression.

Support Vector Machines.

Decision Trees.

Random Forest.

Unsupervised learning: Processing unlabeled data, often used for clustering and dimensionality reduction.

K-Means.

Hierarchical Clustering.

Principal Component Analysis ( PCA ) .

Reinforcement Learning: Agents learn by interacting with the environment and receiving rewards or penalties.

Q-learning.

Deep Q Networks ( DQN ) .

Actor-Critic method.

Proximal Policy Optimization ( PPO ) .

Deep learning: mainly uses neural networks, especially deep networks.

Convolutional neural network ( CNN ) .

Recurrent neural network ( RNN ) .

Long short-term memory network ( LSTM ) .

Transformer structure, such as BERT, GPT, etc.

Definition of Large Model

The concept of "large model" is difficult to define, and there is no widely accepted, official definition so far. The corresponding English word is: "foundation model", also sometimes called: "general-purpose AI" or "GPAI". Refers to a model that can perform a series of general tasks, such as text synthesis, image processing, and audio synthesis. The following are definitions given by some papers or official websites of institutions:

On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models ( 2021 )

In August 2021, Stanford University professor Fei-Fei Li and more than 100 scholars jointly published a 200-page research report "On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models", which deeply reviewed the opportunities and challenges faced by current large-scale pre-training models.

AI is undergoing a paradigm shift with the rise of models ( e.g., BERT, DALL-E, GPT-3 ) that are trained on broad data at scale and are adaptable to a wide range of downstream tasks. We call these models foundation models to underscore their critically central yet incomplete character.

Foundation models are AI neural networks trained on massive unlabeled datasets to handle a wide variety of jobs from translating text to analyzing medical images.

- 5 key features of large models

- Pre-training: using big data and large-scale computing so that it can be used without any additional training.

- General: one model can be used for many tasks.

- Strong adaptability: using narrative text as model input.

- Large: For example, GPT-3 has 175 billion parameters. But as the parameters continue to grow, this standard is also constantly improving.

- Self-supervision: No specific tags provided.

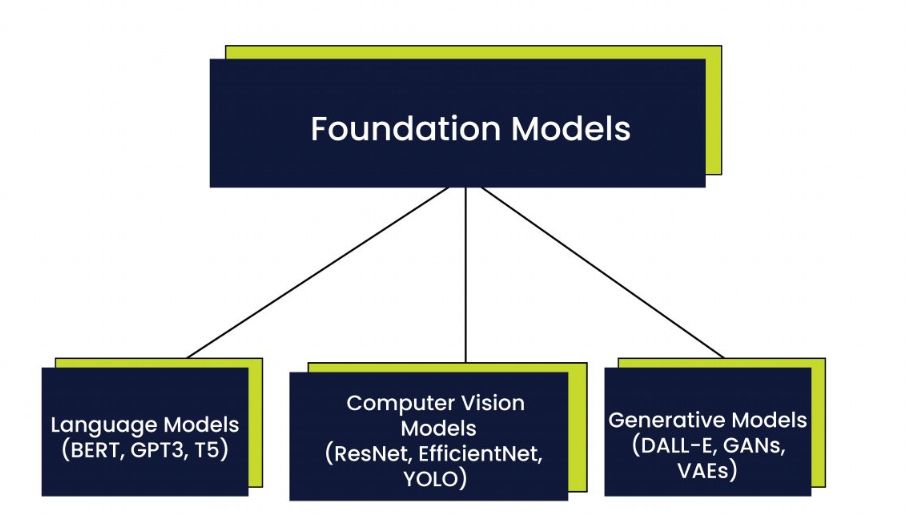

Types of Large Models

Large models can be roughly divided into three types: language models, computer vision models, and generative models. [2]

Language models

BERT

Developed by Google, BERT is a pre-trained language model that is able to understand the nuances of natural language text. According to Google, BERT outperforms previous recurrent neural network ( RNN ) -based language models on a variety of natural language processing tasks, including question answering, translation, sentiment analysis, and predictive text.

GPT3

Developed by OpenAI, GPT-3 is a larger language model that has been trained on a very large dataset. With 175 billion parameters, GPT-3 can generate text that is indistinguishable from human-written text. The model has been used in a variety of applications, including chatbots and virtual assistants.

T5

T5 is a Google The latest language model developed by Microsoft, which takes a different approach to natural language processing. Rather than being fine-tuned for a specific task like BERT, T5 is a general language model that is trained to perform a wide range of tasks, including text classification, question answering, and summarization. T5 uses a unified text-to-text format, which makes it easily adaptable to a variety of natural language processing tasks.

3.2 Vision Models

ResNet

Developed by Microsoft, ResNet is a deep neural network that is able to classify images with very high accuracy. The model has been used in a variety of applications, including image recognition for self-driving cars.

EfficientNet

Developed by Google, EfficientNet is another computer vision model that has achieved state-of-the-art results on a variety of image classification tasks. The model is known for its efficiency and requires far fewer parameters than other leading computer vision models.

YOLO ( You Only Look Once )

YOLO is a real-time object detection system that is able to detect objects in images with very high accuracy. The model has been used in a variety of applications, including self-driving cars and security systems.

3.3 Generative Models

DALL-E

Developed by OpenAI, DALL-E is a generative model capable of creating images from natural language prompts. The model has attracted great interest from the art community due to its ability to generate highly realistic and imaginative images.

GANs

Developed by Ian Goodfellow, GAN ( Generative Adversarial Network ) is a generative model capable of generating new data by pitting two neural networks against each other. An example of such a model is Google's BigGAN, which was trained on a huge dataset of images, enabling it to create generative art with incredible detail and realism. BigGAN has been widely used in advertising, marketing, and even for generating virtual video game environments.

VAEs

VAEs are a generative model capable of generating new data by learning the underlying structure of a dataset. These models have been used for applications such as dimensionality reduction and anomaly detection.

About Training [^model-training]

General Steps

Gather a dataset.

Base models need to be trained on very large datasets, such as text or code. The dataset should be as diverse as possible and should cover the tasks you want the model to be able to perform.

Prepare the dataset.

The dataset needs to be prepared before it can be used to train a model. This includes cleaning the data, removing any errors, and formatting the data in a way that the model can understand.

Tokenize.

Tokenization is the process of breaking text into individual tokens. This is necessary for base models because they need to be able to understand individual words and phrases in the text.

Configure the training process.

Configure the training process to specify the hyperparameters, training algorithm architecture, and the compute resources that will be used.

Train the model.

The model will be trained on the dataset using the specified training model architecture. This may take a long time, depending on the size of the model and the amount of data.

Evaluate the model.

After training the model, you will need to evaluate its performance on a holdout dataset. This will help you determine if the model is performing as expected.

Deploy the model.

Once you are satisfied with the performance of the model, you can deploy it to production. This means making the model available to users so that they can use it to perform tasks.

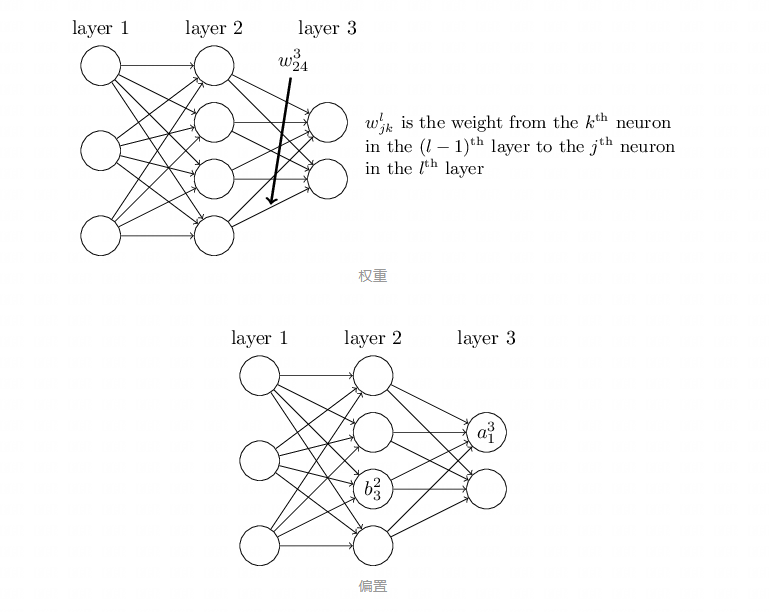

What is an iteration?

An iteration generally consists of the following three steps:

Forward propagation.

Simply put, it takes the output of the previous layer as the input of the next layer and calculates the output of the next layer until the operation reaches the output layer.

Forward propagation Expressed in matrices:

z(l)=W(l)a(l−1)+b(l)

a(l)=σ(z(l))

Where σ is the activation function, such as Sigmoid, ReLU, PReLU, etc.

Calculate the loss.

After the model output is completed, the next step is to evaluate the performance of the model. This is achieved by calculating the loss function. The loss function quantifies the gap between the model prediction and the true label. Common loss functions include cross entropy loss ( for classification problems ) and mean square error ( for regression problems ) The calculation of the loss function is usually expressed as: Loss=f(ModelOutput,TrueLabel).

Backward.

After calculating the loss, the next task is to update the model parameters to reduce this loss. Backward is a method to efficiently calculate the gradient of the loss function with respect to each parameter.

- Calculate gradients: Starting from the output layer, calculate the partial derivatives ( gradients ) of the loss function with respect to the parameters of each layer.

- Update parameters: Use these calculated gradients to update the parameters. New model parameters. Parameters are usually updated using optimization algorithms ( such as gradient descent ) .

NewParameter=OldParameter−α×Gradient

Goals of training algorithms [^paper]

Leveraging broad data

The current massive amount of data generated on the Internet comes in many forms, including text, images, recordings, videos, and robot sensors. Since these data lack additional annotations, current research focuses on designing self-supervised algorithms that use the unique structure of each type of data to generate training signals for the basic model.

Domain completeness

An important goal that large models need to solve is to have broad and useful capabilities for downstream tasks in the domain. This property is crucial to the versatility of large models. However, it is not obvious which tasks will affect domain completeness, and even how to evaluate the breadth of a model is difficult.

Scaling and compute efficiency

The rise of self-supervised algorithms has made the size of models and computing resources increasingly prominent. The efficiency of training can vary greatly between designs, so a major goal of training researchers is to design training objectives with richer training signals so that models learn faster and gain stronger capabilities.

Important Design Choices

Level of Abstraction

A fundamental question is: what should the input representation of the base model be?

- One option is to model the input at the raw byte level. However, this high dimensionality may cause the model to focus on predicting less semantic aspects of the input, slowing down its acquisition of more generally useful features. And its computational cost in the Transformer grows quadratically with the input size.

- Another option is to use domain knowledge to reduce the input space of the model - such strategies include "patch embedding" and fixed or learned tokenization. These methods may alleviate some of the challenges faced by generative methods, but at the cost of discarding potentially useful information in the input.

Generative vs. Discriminative Models

Generative Models Try to learn the joint probability distribution P(X,Y) of the data, where X is the input feature, Y is the label. Examples: GMM, Naive Bayes, HMM, GANs.

Autoregressive base models: When generating sequences ( such as text or music ) , each element is a function of all the previous generated elements.

Denoising base models: These models usually take an input that has been noisy or corrupted in some way, and then try to reconstruct or generate a "clean" version.

While generative training methods have their merits, some discriminative methods have also recently gained attention.

Discriminative models

Try to learn the conditional probability distribution P(Y∣X), that is, the probability of outputting Y given an input X. Examples: Logistic regression, support vector machine SVM, decision tree, random forest, CNN.

Usually perform better in classification tasks and are more computationally efficient. However, they require more data and do not perform as well as generative models when data is scarce.

To better understand the trade-offs between generative and discriminative training, and to capture the best of both approaches, Still an interesting direction for future research.

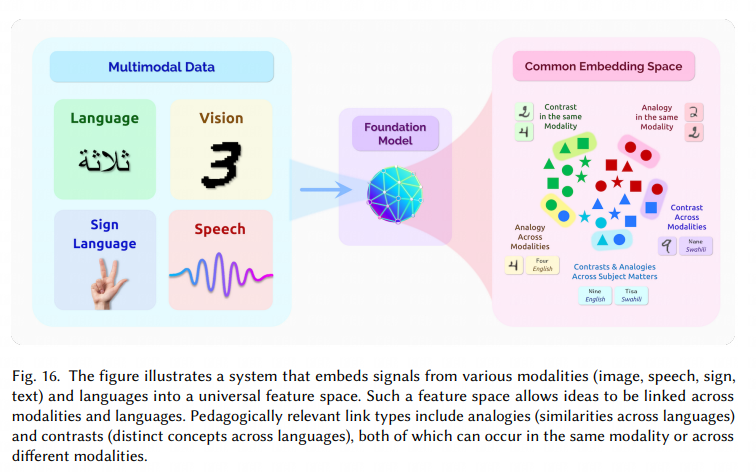

Capturing multimodal relations

Another increasingly important area of research is capturing relations between multiple types of data. This means that the specifics may vary depending on the context and the goals of the model designer. For example, CLIP [Radford et al. 2021] and ViLBERT [Lu et al. 2019a] are both multimodal visual-language models, but differ in how they implement multimodality. The former encodes images and text separately as vectors, allowing users with only samples from a single modality to retrieve, rate, or classify samples from the other modality. The latter processes images and text jointly at an early stage in the model, which helps support downstream applications such as visual question answering, where reasoning about a pair of related images and text ( e.g., an image and its related question ) is required. Multimodal base models are still a new research area; there are still many unexplored questions about how models can be multimodal in different ways and what capabilities these additional modalities can bring.

Challenges

- Data imbalance: The amount and quality of data in different modalities can vary greatly.

- Complexity: Multimodal information usually means higher computational and model complexity.

- Semantic gap: There may be a semantic gap between different modalities, making it difficult to capture the intrinsic correlations between them.

Future Directions [^paper]

Addressing Specificity

Different approaches are currently prevalent in natural language processing, computer vision, and speech processing. This has two major drawbacks: First, these different techniques make it challenging to grasp the common threads and scientific principles underlying each of these approaches. Second, this domain specificity requires developing new base model training methods from scratch for each new domain, including medicine, science, and new multimodal settings.

Obtaining Rich Training Signals

It is clear that not all training objectives are equal - some are more efficient than others, translating into more powerful base models for a given computational budget. Are there more efficient training methods than currently known ones? If so, how can we find them?

Goal-directed training of base models

Can we train base models, Where the ability to understand and reliably execute goals in a complex world is part of the model training goal? Focusing on developing general capabilities distinguishes this direction from the goal of adapting existing base models to specific tasks through reinforcement learning.

Industry Applications [^paper]

Healthcare and Biomedicine

Healthcare Opportunities

For Hospitals

- It can improve the efficiency and accuracy of care provided by hospitals. Such as automatic auxiliary systems for diagnosis/treatment, patient record summarization, and answering patient questions.[Davenport and Kalakota 2019; Nie et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2021b] .

- Especially in urgent pandemic crises such as COVID-19, rapid diagnosis/screening ( e.g., automatic analysis of chest X-ray images ) and automatic question answering for patients and the public ( e.g., symptom checking and care ) and the public ( e.g., disease prevention ) are crucial to reducing disease transmission and allocating healthcare resources to critically ill patients and saving more lives [Lalmuanawma et al. 2020].

- The base model can improve the efficiency and accuracy of provider care. Healthcare providers spend unnecessary time editing electronic health records ( EHR ) [Kocher 2021].

- Preventable medical errors ( e.g., readmissions, surgical errors ) lead to healthcare waste [Shrank et al., 2019; Shah et al., 2020].

For patients

- The large model can provide outpatient appointments and related information. [Bates 2019].

- Answer patient-related questions. [Demner-Fushman et al. 2020].

- Relevant answers to drugs ( multimodal such as text, images, etc. ) [Chaix et al. 2019].

- Question-answering systems for medical problems such as large epidemics ( especially COVID-19 ) [Bharti et al. 2020; Herriman et al. 2020].

Opportunities in biomedicine

The base model can promote biomedical research, For example, drug discovery and understanding of diseases, ultimately translating into improved healthcare solutions [Hanney et al., 2015].

The base model has strong generative capabilities ( e.g., coherent text generation in GPT-3 ) , which can help generative tasks in biomedical research, such as generating experimental protocols ( clinical trials ) and designing effective molecules from existing data ( drug discovery ) [Kadurin et al., 2017; Haller et al., 2019].

The base model has the potential to integrate various data modalities in medicine, enabling the study of biomedical concepts ( e.g., diseases ) from multiple scales ( using molecular, patient, and population-level data ) and multiple knowledge sources ( using imaging, text, and chemical descriptions ) . This facilitates biomedical discoveries that would be difficult to obtain using single-modality data [Lanckriet et al., 2004; Aerts et al., 2006; Kong et al., 2011; Ribeiro et al., 2012; Wang et al. 2014,2015c; Ruiz et al., 2020 ; Wu et al., 2021h].

The base model also supports cross-modal knowledge transfer. Lu et al. [2021a] showed how a transformer model trained on natural language ( a data-rich modality ) can be adapted to other sequence-based tasks, such as protein folding prediction, a long-studied prediction task in biomedicine [Jumper et al., 2020].

Challenges and Risks

Multimodality.

Medical data is highly multimodal, with a variety of data types ( text, images, videos, databases, molecules ) , scales ( molecules, genes, cells, tissues, patients, populations ) , and styles ( professional and non-professional languages ) . Current self-supervised models are developed for each modality ( e.g., text, images, genes, proteins ) and do not learn different modalities jointly. To learn cross-modal and cross-modal information from these different multimodal medical data, we need to study feature-level and semantic-level fusion strategies in base model training. If done effectively, this has the potential to unify biomedical knowledge and promote discovery.

Interpretability.

Interpretability—providing evidence and logical steps for decision making—is critical in healthcare and biomedicine and is mandatory under the General Data Protection Regulation ( GDPR ) . For example, in diagnostics and clinical trials, patients』 symptoms and temporal correlations must be explained as evidence. This helps resolve potential disagreements between the system and human experts. Interpretability is also required for informed consent in healthcare. However, current training objectives for base models do not include interpretability, and future research in this direction is needed. Incorporating knowledge graphs could be a step to further improve model interpretability.

Legal and ethical regulations.

Extrapolation.

The process of biomedical discovery involves extrapolation. For example, base models must be able to quickly adapt to new experimental techniques ( e.g., new assays, new imaging techniques such as high-resolution microscopy ) or new settings ( e.g., new target diseases such as COVID-19 ) . The ability to leverage existing datasets and extrapolate to new settings is a key challenge for machine learning in biomedicine. While GPT-3 exhibits some extrapolation behavior ( e.g., generating new text that has never been seen before ) , its mechanisms are unclear and still in their infancy. Further research is needed to improve the extrapolation capabilities of the base model, especially when considering the diverse data patterns and tasks inherent to healthcare and biomedicine, but not typically studied in current GPT-3 and related models.

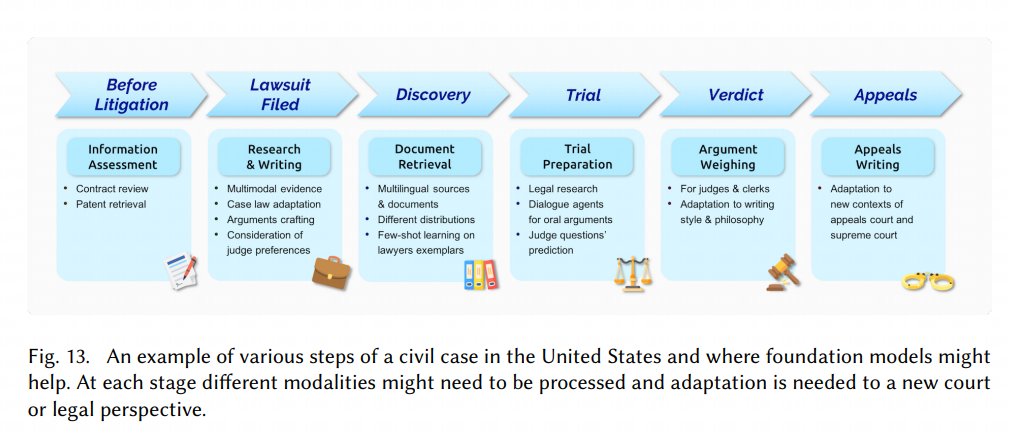

Law

Opportunities

Unique Advantages of Large Models

Learning with Limited Annotations:

The cost of annotating data is very high. Typically, the expertise to produce high-quality labels can only be found in lawyers, who charge hundreds of dollars per hour. Even after obtaining labels, some data may be erroneous, sensitive, and cannot be pooled together to train a large language model. Given recent advances in few-shot learning [Brown et al. 2020], base models are one of the most promising paths for learning models with limited annotations.

Large amounts of historical data:

Legal decision-making requires context at different scales: all the historical knowledge of judgments and standards, knowledge of case law that still applies to the present, and understanding of the nuances of the individual case at hand. The base model is likely to learn a common representation of the history and legal context to model the language ability and accuracy of individual cases.

Challenges and Risks

Long text narratives.

The length of the statement documents used in US courts is usually between 4,700 and 15,000 words. A case review document usually reaches 20,000 to 30,000 words. The current large model cannot reach this length for long text generation.

Retrieval, concept drift, argument formation and logical reasoning.

The current large model is weak in the logical reasoning part of the argument.

Accuracy.

The base model creates false facts in the process, which is an existing problem in current models [Gretz et al. 2020; Zellers et al. [2019b]]. Specificity and authenticity are two different things, which are particularly important in the legal environment, where imprecise statements can lead to drastic, unexpected consequences and false statements can lead to sanctions against lawyers.

Adaptability.

Different legal tasks may require different training processes, and adaptability is currently poor.

Education

Opportunities

Challenges and risks

Determine whether the student's homework is generated by AI.

VSCode launched CoPilot, which affects the physical examination of programming beginners.

Privacy and security

In the United States, student information, especially for children under 13 years old, is particularly important. FERPA restricts teachers from sharing student homework, which may directly affect the initiative of data used to train and evaluate basic models. Including whether the weights of the basic model will leak data in some way. [Nasr et al. 2018; Song et al. 2017].

Figure from Figure 2 in DEEP REINFORCEMENT LEARNING ↩︎

Foundation Models 101: A step-by-step guide for beginners [^model-training]: What it Takes to Train a Foundation Model [^paper]: On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models ( 2021 ) ↩︎

Contributors

Changelog

Copyright

Copyright Ownership:dingyuqi

License under:Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC-BY-NC-ND-4.0)